Poster Presentation The 13th International Congress of the Immunology of Diabetes Society 2013

Increased weight or height gain in infants/toddlers does not predict early development of T1D: The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) Study (#113)

Increased body size, particularly obesity, has been postulated to increase the risk for T1D (accelerator hypothesis). We assessed the relationship between growth in the initial two years of life and development of early childhood diabetes in a large prospective cohort.

TEDDY follows from birth 8,502 genetically high-risk children from Sweden, Finland, Germany and the USA. Of those, 8,159 had complete data available, including 148 children who have developed T1D during the median 5.9 years of follow-up (range 3.4-8.9 yr). Weight and height measurements were converted to z-scores. Piecewise quadratic polynomial mixed models were used to derive best linear unbiased predictors for a child’s growth curves from birth up to 8 years of life. Cox proportional hazard models generated T1D hazard ratios (HR) for z-scores of weight and height from 0-12 or 0-24 months of age.

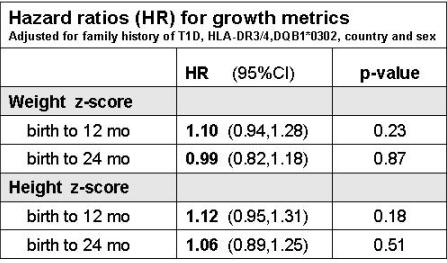

The median age at diagnosis of T1D was 3.0 yr (interquartile range 2.0-4.6). The independent predictors of T1D included: history of T1D in a first degree relative (HR=3.95; 95%CI 2.74-5.70), the HLA-DR3/4,DQB1*0302 genotype vs. other high-risk HLA genotypes (HR=2.18; 1.57-3.03) and residence in Finland, Sweden or Germany vs. the US. Controlling for these potential confounders and sex, the risk of developing diabetes was not related to weight or height during the initial one or two years of life (Table). Weight, height and BMI z-scores obtained 3, 4, 9 and 12 months prior to T1D diagnosis were also not different from those in 8,011 children who remained diabetes-free.

TEDDY found no evidence that faster growth or weight gain in the initial two years of life contribute to development of T1D in early childhood.

Funded by NIH, NIDDK, NIAID, NICHD, NIEHS, JDRF and CDC.